Rural Alaskans enjoy hunting and fishing privileges on federal lands to sustain their way of life.

The decisions for opening and closing hunting grounds and setting harvest limits are decided by the more than 100 Alaskans who sit on 10 regional advisory councils (RAC) that inform the Federal Subsistence Board.

“They’re the ones that are on the ground and making these observations based upon a lifetime of experience,” said Jim Fall, who until recently was the state’s head of subsistence research.

He recently retired from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game after 39 years of service. And he’s been to a lot of these council meetings where a wide-ranging group from across regions have frank and full discussions about the state of wildlife populations, fish stocks and observations about what’s happening in their communities.

“The broader representation you have at a regional council, the better those ideas are,” Fall said.

But this year there are going to be fewer voices at the table. That’s because more than half of the seats are now unfilled. It’s not due to lack of interest. The federal Office of Subsistence Management (OSM) says it dutifully forwarded enough names last fall to the U.S. Secretary of the Interior.

“We still have 35 open seats on all RACs, which means that 56% of 2020 open seats were not filled,” wrote OSM Acting Policy Coordinator Katya Wessels in a recent briefing to the Federal Subsistence Board. “Some RACs now have as many as eight open seats.”

Many of those whose appointments were stalled are long-serving members.

Until the end of last year Don Hernandez has chaired the Southeast RAC. His reappointment has been inexplicably held up and he’s gotten no explanation.

“Either they’re not telling us or they don’t know,” Hernandez said from his home in Point Baker on the northern tip of Prince of Wales Island. “So we don’t even know who to call.”

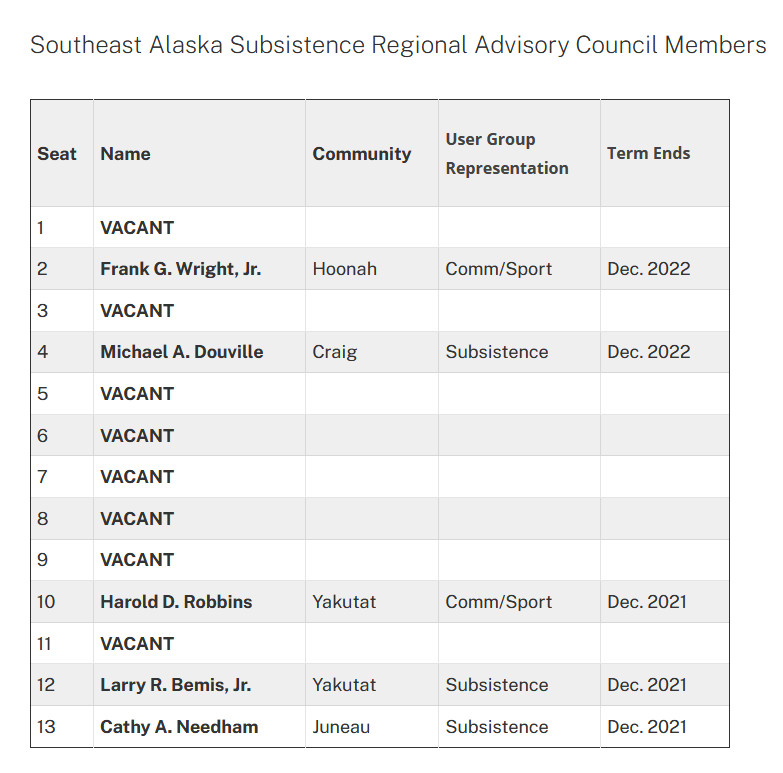

That leaves the Southeast’s 13-seat regional advisory council with five members.

“And that’s just not a real good representation for all of the different issues that we have here in Southeast Alaska,” he said. “So it’s going to be really tough to get anything done at this next meeting, I’m afraid.”

It’s not just Southeast that’s struggling to fill seats. The Western Interior regional council stretches a across a large chunk of landlocked territory from Aniak on the Kuskokwim River to the Brooks Range.

“It’s a huge area, it’s like multiple states,” said Jack Reakoff, who lives in remote Wiseman, a former mining camp roughly halfway between Fairbanks and Prudhoe Bay. He was on he board from its inception in 1993. But not anymore; his reappointment was inexplicably held up on the eve of the spring meeting later this month.

“They’re going to be completely overwhelmed for this meeting,” he said.

Who is or what is responsible for the break down in appointments isn’t clear. A Trump administration executive order signed in mid-2019 directed federal agencies to reduce or eliminate advisory boards considered obsolete, duplicative or expensive.

But what is clear is that the Trump administration’s Interior Secretary chose not to fill 35 seats late last year. The recent change in presidential administrations has added yet another layer of uncertainty with people in the federal agencies scrambling for answers.

The Interior Department headquarters in Washington D.C. declined to comment.

The Office of Subsistence Management is soliciting nominations now, but it’s a year-long process. And applicants who file by the February 15 deadline likely won’t be seated until 2022.

There have long been tensions between the rights of rural subsistence hunters and the state over priority for rural subsistence users. Some of those conflicts have recently wound up in court.

Reakoff says there are political actors who have long been hostile to subsistence rights that would cheer the dismantling of the regional advisory councils.

“Rural subsistence priorities have never been palatable to the state of Alaska,” Reakoff said.

Rick Green, an assistant in the Alaska Department of Fish and Game Commissioner’s Office, says the state is neutral on the stalled nomination process.

“That is their process to carry out,” Green wrote in a statement to CoastAlaska. “As for their public meetings, yes there is value to state managers as they bring parties interested in conservation of our resources together for public comments and suggestions and any group that brings the public together for the shared goal of conservation of our trust properties is useful.”

Subsistence priorities are enshrined by ANILCA — that’s the landmark legislation signed into law by President Carter — that expanded national parks and monuments in Alaska, but also guaranteed Alaskans have some decision making authority over subsistence rights on federal lands.

“The regional advisory councils are kind of the linchpin of the whole system,” Hernandez said. “Having good functioning, well-qualified advisory councils is the key to make the whole subsistence system work in Alaska.”

But whether the lack of appointments is due to bureaucratic inefficiencies or political wranglng, the outcome will be the same: less input on federal wildlife management decisions by the people whose lifestyle and livelihood depend on it.

This story has been updated to add that the Interior Department declined to comment.