On Saturday a man attempted to swim from Mitkof Island in Southeast Alaska to the mainland. It’s about six miles across from where he started at Sandy Beach in Petersburg.

“There’s no reason good reason for me to do this. This is a bunch of nonsense,” says Andrew Simmonds. “But this is what one does. When one has nothing else going on in their life. It’s pretty simple. They do things like this.”

Simmonds is walking out Sandy Beach at eight in the morning. He’s in a 5 mm hooded wetsuit, gloves, booties, goggles, and a fluorescent green swim cap. He has a diving knife and a waterproof radio strapped to him. He’s about to try to swim across Frederick Sound – almost six miles from here to the mainland.

He doesn’t know how far his body temperature will drop after several hours in 51 degree water, or which way the currents are going. The farthest he’s ever swum before is two miles in a pool. And, he’s 60 years old.

He wades out into a thick fog, and starts up a slow, steady stroke.

Simmonds is a physical therapist at the Petersburg Medical Center. He’s originally from New York, and says he spent the first 55 years of his life within a 100 mile radius. When his son went to college, Simmonds joined the Peace Corps and began to travel – South Sudan, Haiti, then Sitka and Hawaii. He swam in the big waves in Hawaii, and liked it, so when he came to Petersburg in November 2021 he started training in the pool to improve his freestyle stroke. A few months later, he got the idea to swim across Frederick Sound.

Josef Quitslund agreed to spot him in a boat. “I thought he was crazy,” Quitslund says, “but I knew that he could do it.”

The two of them are at the bar, decompressing after the long, wild day.

When they started crossing the Sound, everything went smoothly. It was flat and calm. They could hear each other well. Around halfway across, Simmonds started thinking that maybe this would be a piece of cake.

But by about six hours in Simmonds, who weighs about 155 lbs, was getting seriously cold.

“Once we got into the iceberg area,” Simmonds says, “I bumped into a piece of ice, which freaked me out a little bit because I thought it was a marine mammal coming to eat me.”

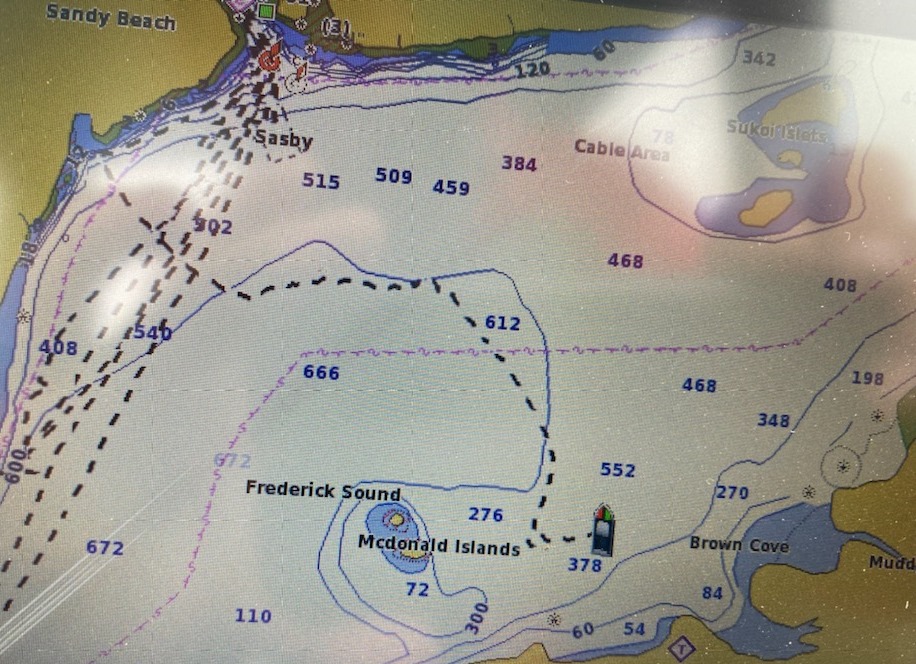

They had reached just northeast of the McDonald Islands, and chunks of the LeConte glacier were floating by. Simmonds swam harder to warm himself up. He could tell he was losing function and mental clarity. A strong offshore surface current was pushing against him. On the boat, the GPS showed they were in fact moving backwards. But the shore was less than three quarters of a mile away. Simmonds didn’t want to stop.

“I was pulling harder at that point than the whole time over,” he says. “I was kicking harder, pulling harder and going . . . nowhere.”

Finally, after seven and a half hours in the ocean, he decided to climb up the ladder onto the boat while he still could.

“He was at the point where he really needed to come out, but he was still coherent,” says Quitslund. “And you know, he was under his own power.”

Simmonds drank some hot cocoa, and when he got home he celebrated by listening to some hard rock. He says he feels like a million bucks.

“The target wasn’t hit, but it was a success,” he says. “I faced the demon, I faced the dragon.”

Simmonds is already planning his next attempt, deconstructing the factors to determine what to adjust. He has no interest in trying a shorter or easier route.